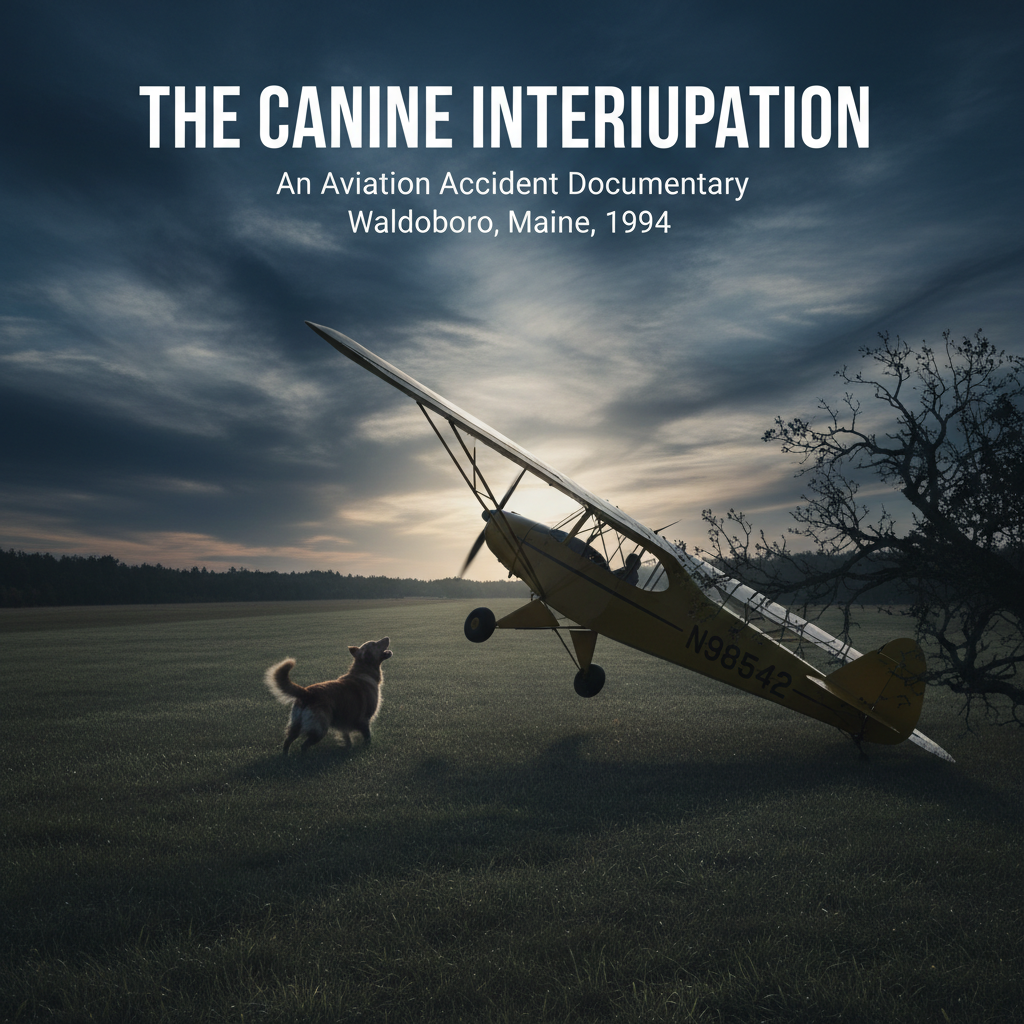

**The Canine Interruption**

The small Piper J3C, a classic tailwheel aircraft, rumbled down the grass runway, gaining speed. It was a crisp November afternoon in Waldoboro, Maine, 1994. Harry Bickford, a student pilot with 110 hours in his logbook, was at the controls, preparing for what should have been a routine local flight. But as the yellow Cub accelerated, a sudden, unexpected distraction erupted onto the scene, irrevocably altering the flight’s trajectory.

It was Bickford’s own dog, playfully, perhaps, but dangerously, chasing the plane down the runway. A split-second decision, born of instinct and concern, would now unfold.

The Piper J3C, registration N98542, was a quintessential general aviation aircraft, known for its docile handling and short-field capabilities. Yet, even the most forgiving aircraft demands precise adherence to fundamental principles, especially during critical phases of flight like takeoff. Bickford, a 56-year-old student pilot, was the sole occupant. The weather was clear, visual meteorological conditions prevailing, offering no external complications to the flight.

As the aircraft rolled, the pilot, distracted by his dog, found himself off the ideal center line. The Piper was slow, not yet at its optimal liftoff speed, when Bickford made the crucial choice. To avoid striking his beloved pet, he pulled back on the controls, lifting off prematurely. The aircraft, lacking sufficient airspeed and climb performance, struggled to gain altitude.

Then, the collision. The right wingtip, still perilously low, strikes a tree at the end of the runway. The impact is sudden, jarring. The aircraft lurches, its delicate balance shattered. The right wing, now compromised, loses lift, stalling. The Piper, no longer flying, pitches down violently. The left wing, then the engine, strikes the unforgiving terrain.

The Piper J3C, once a symbol of leisurely flight, now lay substantially damaged on the ground. Miraculously, the pilot, Harry Bickford, emerged uninjured from the wreckage, a testament to the robust, albeit simple, construction of the Cub.

The subsequent investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board meticulously pieced together the sequence of events. The pilot’s own account confirmed the critical distraction: “I did not get lined up for takeoff the way I should because of the dog chasing the plane… The plane was going slow and as I neared the end of the runway my right wing tip hit a tree.” The FAA inspector’s findings corroborated this, highlighting the premature liftoff to avoid the dog, leading directly to the collision with the trees.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of this accident to be the pilot’s premature liftoff, which resulted in insufficient climb performance and a collision with trees. Contributing factors included the pilot’s diverted attention and his failure to maintain adequate clearance from the obstacles.

This incident serves as a stark reminder of the unforgiving nature of aviation, where even a momentary distraction, a well-intentioned but ill-timed decision, can unravel a routine flight. It underscores the critical importance of maintaining focus during takeoff, ensuring the aircraft reaches its proper flying speed, and adhering to established procedures, even when faced with the most unexpected and emotionally charged interruptions. The safety legacy of this event reinforces the fundamental principle that the pilot in command bears the ultimate responsibility for the safe operation of the aircraft, free from all distractions, especially during the most critical phases of flight.